Ebola Virus Infection

What is Ebola?

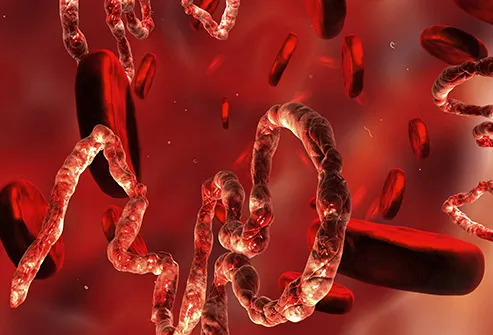

Ebola is a deadly disease caused by a virus. There are five

strains, and four of them can make people sick. After entering the body,

it kills cells, making some of them explode. It wrecks the immune

system, causes heavy bleeding inside the body, and damages almost every

organ.

The virus is scary, but it’s also rare. You can get it only from direct contact with an infected person’s body fluids.

The virus is scary, but it’s also rare. You can get it only from direct contact with an infected person’s body fluids.

Perhaps no virus strikes as much fear in people as Ebola, the cause of a deadly outbreak in West Africa.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports more than 14,400 confirmed or suspected cases of Ebola, mostly in the countries of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, as of Nov. 11. More than 5,100 people have died in the largest Ebola outbreak ever recorded.

Four confirmed or probable cases have been reported in Mali, along with three deaths, the WHO said.

A surgeon from Sierra Leone who lives in the United States died after being flown to the Nabraska Medical Center for treatment, the hospital said Nov. 17.

Martin Salia, who was reportedly working at a hospital in the Sierra Leone capital of Freetown, arrived in the U.S. Nov. 15 and was taken to the medical center.

He was in extremely critical condition, suffering from kidney and respiratory failure, when he arrived, the hospital said.“We used every possible treatment available to give Dr. Salia every possible opportunity for survival,” said Phil Smith, MD, medical director of the hospital’s biocontainment unit. That included giving him the experimental treatment ZMapp, also given to other Ebola patients, according to the hospital.

But Salia’s disease was “extremely advanced,” Smith said in a statement.

Salia was reportedly a permanent U.S. resident who lived in Maryland with his family.

Two other Americans – Rick Sacra, MD, and Ashoka Mukpo – recovered from Ebola after being treated in the Omaha isolation unit.

A Doctors Without Borders physician who returned to the U.S. after treating Ebola patients in Guinea was the latest person in the U.S. to be diagnosed with Ebola. Craig Spencer, MD, recovered after getting treatment at New York’s Bellevue Hospital. He was released on Nov. 11.

Spencer, who returned to New York on Oct. 17, was taken to the hospital 6 days later after reporting a fever and vomiting

Two nurses at a Dallas hospital also caught Ebola after treating Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian man who later died. The nurses, Nina Pham, 26, and Amber Vinson, 29, both work at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital. Duncan arrived in the U.S. on Sept. 20 to visit relatives and 10 days later became the first person to be diagnosed with Ebola in the U.S. He died Oct. 8.

Both Pham and Vinson recovered from the virus and have been released from hospitals. No one who had contact with them, including people on flights Vinson took from Cleveland to Dallas and back before being admitted to a hospital, caught Ebola.

In total, five Americans infected with the virus in Africa have been brought back to the U.S. for treatment. All have recovered. The five include aid workers Sacra, Kent Brantly, MD, and Nancy Writebol.

The fourth person was flown back to the U.S. on Sept. 9 for treatment at Atlanta’s Emory University Hospital, where Brantly and Writebol were also treated. This person's arrival came after the WHO said one of its doctors was being evacuated from Sierra Leone after getting Ebola. The man was released from the hospital Oct. 19. He wants to remain anonymous, the hospital said.

Mukpo, a freelance cameraman for NBC News, was flown to Omaha on Oct. 6. He was part of a crew covering the outbreak in West Africa. He was released Oct. 22.

Ebola Outbreak Unfolds in Africa

On Aug. 8, the WHO declared the Ebola outbreak in West Africa to be a “public health emergency of international concern.” It said “a coordinated international response is deemed essential to stop and reverse the international spread” of the virus.On Sept. 16, President Barack Obama announced a plan to scale up the nation’s response to the Ebola crisis in West Africa. Responding to a plea for help from the Liberian government, Obama said the Department of Defense will send personnel there to boost the international response to the outbreak. The U.S. will also build 17 100-bed units to treat Ebola patients.

Ebola was first identified in 1976, when it appeared in outbreaks in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is named for the Ebola River, which runs near the Congolese village where one of the first outbreaks happened.

WebMD asked Amesh Adalja, MD, about the virus and efforts to contain it. Adalja is an infectious disease doctor at the University of Pittsburgh.

Q. How deadly is Ebola?

A. The Ebola strain in the current outbreak is the most lethal of the five known strains of the virus. It is called Ebola Zaire and usually kills up to 9 out of 10 infected people. But the high death rate might be due to a lack of modern medical care, Adalja says. “It’s hard to say exactly what the [death] rate would be in a modern hospital with all of its intensive care units.”

The CDC said in July the Ebola death rate in the West African outbreak is about 6 in 10, rather than 9 in 10. That shows that early treatment efforts have been effective, says Stephan Monroe, deputy director of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases at the CDC.

On July 31, the CDC issued a travel advisory recommending against non-essential travel to Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

Q. What are the symptoms?

A. At first, the symptoms are like a bad case of the flu: high fever, muscle aches, headache, sore throat, and weakness. They are followed quickly by vomiting, diarrhea, and internal and external bleeding, which can spread the virus. The kidneys and liver begin to fail.

Ebola Zaire kills people quickly, typically 7 to 14 days after symptoms appear, Adalja says.

A person can have the virus but not show any symptoms for as long as 3 weeks, he says. People who survive can still have the virus in their system for weeks afterward.

The virus has been detected in semen up to 7 weeks after recovery, according to the WHO. But this is very rare, says Thomas Geisbert, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Texas Medical Branch. Geisbert has been studying the Ebola virus since 1988.

Q. How does the virus spread?

A. Ebola isn’t as contagious as more common viruses, such as colds, influenza, or measles, Adalja says. It spreads to people by close contact with skin and bodily fluids from infected animals, such as fruit bats and monkeys. Then it spreads from person to person the same way.

“The key message is to minimize bodily fluid exposures,” Adalja says.

Q. What precautions should people take if they’re concerned they might come in contact with someone infected with Ebola?

A. “Ebola is very hard to catch,” Adalja emphasizes. Infected people are contagious only after symptoms appear, by which time close contacts, such as health care workers and family members, would use “universal precautions.” That's an infection control approach in which all blood and certain body fluids are treated as if they are infectious for diseases that can be borne in them, Adalja says.

Even though the virus can be transmitted by kissing or sex, people with Ebola symptoms are so sick that they’re not typically taking part in those behaviors, he says.

Q. Is there a cure or a vaccine to protect against it?

A. No, but scientists are working on both. The National Institutes of Health is taking part in human testing of an experimental Ebola vaccine, which began in early September. Testing for that vaccine is also taking place in the U.K. and Mali.

The agency expects to have results of that trial by the end of 2014. The NIH is also testing several other potential vaccines.

There is no specific treatment for Ebola. The only treatments available are supportive kinds, such as IV fluids and medications to level out blood pressure, a breathing machine, and transfusions, Adalja says.

ZMapp was given to Brantly and Writebol, among others. But health officials don't know if it aided in their recovery. A trial of ZMapp in 18 Ebola-infected rhesus monkeys prompted recovery in all 18, researchers reported.

Sacra received a different treatment, called TKM-Ebola. He also received a blood transfusion from Brantly, a friend. Health officials don't know if any of these treatments helped with his recovery.

Duncan and Mukpo both received an experimental drug named brincidofovir. The drug is being tested for effectiveness against cytomegalovirus and adenovirus, but test-tube experiments done at the CDC and National Institutes of Health reveal it showed effectiveness against Ebola, according to its manufacturer, Chimerix Inc.

Mukpo and Pham also received blood transfusions from Brantly.

Spencer was reportedly given a range of treatments, including an experimental drug and a blood transfusion from Writebol. The experimental drug was not identified.

Q. Why do some people survive the virus?

A. That’s hard to say. Adalja thinks several things might play a role, such as a person's age and genetic makeup, and whether they have other medical conditions. Those aren't proven reasons, though.

Q. How can the outbreak be stopped?

A. Simple steps to control infection, such as gowns, gloves, and eye protection, can help halt the spread of Ebola, Adalja says. Public health officials will have to wait 6 weeks after the last case is reported before declaring the outbreak over, he says.

Keys to stopping Ebola include identifying patients; providing treatment, preventing the spread, and protecting health care workers, including following patients’ contacts and monitoring them for symptoms; and preventing future cases through education and urging people to avoid close contact with sick people or bodies, Frieden has said.

But, he said, turning the tide in Western Africa is “not going to be quick or easy. Even in a best-case scenario, it would take 3 to 6 months or more.”

Q. Could an Ebola outbreak happen in the United States?

Although concerns have grown since Sept. 30, when the first case was diagnosed in the U.S., health officials have continued to say they are well-prepared to deal with Ebola, and that the risk of an outbreak remains low.

“I have no doubt that we will control this importation or this case of Ebola so that it doesn’t spread widely in this country,” Frieden told reporters on Sept. 30.

The first case diagnosed in the U.S. was “not unexpected,” says William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Nashville’s Vanderbilt University Hospital. “There’s a lot of travel between West Africa and the United States, and we all anticipated that sooner or later there would be a traveler exposed.”

Measures are being taken to isolate members of the man’s family and track others he was in contact with.

One of the five Ebola virus strains caused an outbreak in laboratory monkeys in Reston, VA, outside Washington, DC, in 1989. People who were exposed to that strain of Ebola virus did not get sick. But they developed antibodies to it.

Reviewed by

Michael W. Smith, MD on November 17, 2014

0 comments:

Post a Comment